Adina Ionescu Muscel - Art photography and mixed media

The sessile plant

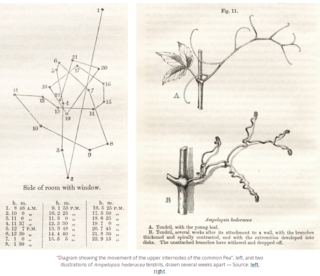

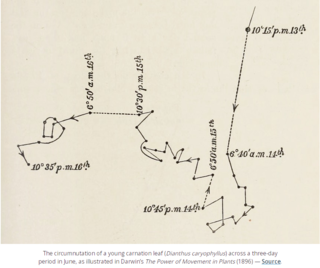

Darwin developed a way of recording the movements of individual parts of plants as they grew and rotated through space. He placed a plant between a sheet of paper and a glass plate and marked a reference point on the paper, attaching a thin wire to a particular part of the plant, such as a leaf or bud. He made recordings at regular intervals by lining up the end of this filament with the fixed reference point, and then marking its position on the glass plate. Seeing Darwin’s strange, angular drawings without any context, it would be easy to think that they might be the tracks of a small animal — a woodlouse, beetle, or perhaps a mouse with a short attention span. They seem like the staccato perambulations of a creature that does not have a clear purpose, rambling across the paper. But that is because these are static, two-dimensional renderings of movements that occurred in three dimensions.

After many hours during which multiple points were recorded, Darwin could then trace the plant’s movement over time by connecting the dots on the plate in order. In this way, he made the movement visible to the naked eye. Darwin could even magnify movements by varying the distance between the plate and the plant. By moving it further away, he increased the angle at which the points aligned to his eye, thus stretching small movements across larger distances on the plate. In the days before time-lapse photography and cinematography, this was an incredibly creative way of capturing plant movement to make it meaningful for humans.

The rotting logs, field mushrooms, crumbling leaves, ancient sands and greening grass are not discreet things; they are happenings taking shape through deep time and the ephemera of now and now and now.

Green beings are to be understood as practitioners of a kind of alchemical cosmos mattering; we think that plants can’t move, but they reach across the cosmos, dawning the energy of the sun into their tissue so that they can work the terrestrial magic.

Pulling matter out of the air, plants could be understood as the world-making conjurers; they teach us the most nuanced lessons about matter and mattering.

They know how to compose livable, breathable and nourishing worlds: as they exhale, they compose the atmosphere, as they decompose, they matter the compost and feed the soil, holding the earth down and the sky up, they sing in nearly ultrasonic frequencies as they transpire moving massive volumes of water from the depths of the earth up to the atmosphere; they cleanse the waters and seed the clouds.

They breathe us into being.

Natasha Meyer

Some plants, such as mimosa or Venus fly traps, have very specific, seemingly responsive movements that are hard for animal senses to ignore. But most plant behaviour, which may even betray an intelligence that we are only just starting to investigate, goes totally unnoticed. What Darwin really did was see plants in a new way: to look from their perspective and observe how their movement and behaviour benefitted them. It was a project which he never quite put down.

“We think the sagebrush are basically eavesdropping on one another,” Karban said. He found that the more closely related the plants the more likely they are to respond to the chemical signal, suggesting that plants may display a form of kin recognition.

The Sessile Plant

Unable to run away, plants deploy a complex molecular vocabulary to signal distress, deter or poison enemies, and recruit animals to perform various services for them. A recent study in Science found that the caffeine produced by many plants may function not only as a defense chemical, as had previously been thought, but in some cases as a psychoactive drug in their nectar. The caffeine encourages bees to remember a particular plant and return to it, making them more faithful and effective pollinators.

JavaScript is turned off.

Please enable JavaScript to view this site properly.